Tuesday, February 22, 2011

Dealing with Addiction: Victorian Fiction

All right. A week or two ago, after plenty of challenging, edifying, or at last worthwhile literature, I felt a hankering for something else, a "little bit on the side" as our grandfathers called their favored brothel playmates, and so I dropped by one of our local Half Price Books (the sites of so many of my crimes) for another copy of Wilkie Collins's The Woman in White (discussed in an earlier post; see below). I did this despite the fact that I already had, god only knows where, three other copies of that book, but I figured I could get a copy of such a classic (read: overprinted) novel cheaply, thus obviating the need to go through box after box in my garage or storage unit.

This one was a Wordsworth Books edition, the cheapest of the cheap public domain publishers (and thanks!), and now part of their "Tales of Mystery & the Supernatural" series designed to catch browsing book-buyer's macabre eyes. That's not important; just thought I'd mention it.

However, this momentary (or so I thought) backsliding into the clutches of Victorian literature (sensation fiction, of all things!) was not, alas, to leave me unmarked. Before seven days had passed I'd reread both The Moonstone and Phineas Finn--Phineas Finn, the goddamned Irish Member himself!--and as if that weren't bad enough, I'd bought an Oxford Illustrated Classics edition (at least I got a good price for it) of The Mystery of Edwin Drood--fortunately for me, I did not read that particular opus imperfectum again, nor do I plan to until middle age.

I was only able to begin pulling myself out of this binge through a judicious and liberal application of Thomas Hardy (Far From the Madding Crown, The Woodlanders--now is clearly not the time to finally read Desperate Remedies) as shock treatment. After all, Wessex is a nice place to go if you've got to sober up.

So what is it about Victorian literature that attracts the weak among us? I think it probably has a lot to do with being able to take the whole thing as a big joke--"respectable" (and even not so respectable) fiction of the period comes off to modern eyes and ears as very near to satire of itself. To take one glaring problem with these people, they never have sex, nor seem to want to. All quote desire unquote is confined to some sort of abstracted transcendental sentimentality, usually as a device for tortured and tortuous thoughts and machinations on the part of an important to character (i.e., "I have loved him always, secretly in my heart of hearts: How thus could I betray him, guilty though he be of such enormity?" blah blah blah).

Maybe there's always some kind of gap between the fictional world produced by a culture and what was really going on in that culture, at least for the most part, but the Victorian Era in the UK and US (but esp. in the UK!) enlarged this discrepancy to alarming proportions. The fact is, we know people were fucking: fucking each others's brains out in privies, in the servants's quarters, the garret, the summerhouse, behind the folly in the park, against every smooth-barked tree, etc. We know this because a few people managed to confess to us, posterity, what they were not supposed to tell us and what they couldn't to any significant degree publicly tell each other during their lives, for example in "Walter's" My Secret Life--shockingly unfelicitous in expression, but as honest an account of a man's sex life as I've read or heard.

But sex is just the most glaring and obvious of the self-imposed blindnesses of those times. And who knows (though if it's anybody's job to tell us, it's artists's) what our blindnesses are today? Still, that's no excuse for these people, nor for the thusly compromised works of fiction that they produced. Rare is the mainstream Victorian novel that can be read as "great literature" today; mostly, they seem to be read for their social, historical, or formal significances. There are obvious exceptions: Hardy, certainly; Thackeray, maybe; Eliot, probably, by a hair.

This isn't to say that I don't think there was a lot of innovative work done by other Victorian novelists, nor that there was not a great deal of very good writing--passages from works by Dickens and Trollope et al. are among the most evocative writing in any language, ever; I'm confident of that--but all the same it's hard to read them without thinking something like, "Oh, I like that. I bet I'd really have liked this book when I was nine or ten." Always supposing one had to hand any requisite reference works, which fortunately children now do thanks to the Internet. By the way, I think people of about my age were the last people who didn't learn to read after understanding the important reference role of the WWW--at least, that's what I hope.

Richard Brautigan's "The Hawkline Monster: A Gothic Western"

A deliberate perversion; wicked, boyish, joyful.

(It's come to my notice that I've been giving a lot more of my time to British and specially English writers than they probably deserve. This is an attempt to partially correct this.)

Brautigan didn't have much time for what other people thought, nor for what they wrote or might expect him to write, as the other two books of his that I've read--The Abortion: An Historical Romance 1966 and Rommel Drives On Deep Into Egypt (a book of poems)--demonstrate. Here is the opening verse (I might better say "salvo") of that latter volume:

Rommel is dead.

His army has joined the quicksand legions

of history where battle is always

a metal echo saluting a rusty shadow.

His tanks are gone.

How's your ass?

Almost a little like something out of Robert Lowell, until the last line of course.

Actually, Brautigan didn't have much time, period, for caring what people thought or anything else in the grand scheme of things: alone, 49 years old in a big old house in Bolinas, CA, Brautigan blew his cranium open with a .44 Magnum revolver just like Dirty Harry's--(probably) 10 years to the day after Hawkline was published, but we can't be sure because although that was the last time anybody heard from him (a bad conversation with an ex-girlfriend a long way away) his body wasn't found until a month and a half later, by a private investigator. He was survived by both parents, both ex-wives, and a daughter.

Actually, I don't know very much about Brautigan; he seems like a literary character who also wrote stuff, a character of the mischievous and "deliberately enigmatic" sort. Then again, it has to be said in his defense that he seems to have made literature fun--at least for a while, and at least for him. One thing that I think I can fairly say from having read these books and looked at their original covers (Hawkline a notable exception to this rule) is that Brautigan loved beautiful women, or at least pretty ones (tastes do vary, and each year seems to have it's own paradigm). I'd like to think that he also got along (to put it one way) with them: such a fact would, esp. given his gangly and generally unbecoming appearance, give some encouragement to those wondering if literature is a worthwhile pursuit and credence to those immortal words spoken by Sean Connery in Finding Forrester.

It strikes me that, so far, I haven't written anything at all about the book whose title appears above this post. That is, perhaps, unfortunate, but at the same time it's symptomatic of reading Brautigan. I can honestly say that I enjoyed this book: I enjoyed reading it, I enjoyed holding it, I enjoyed putting it down and finally placing it back on my shelf. I even laughed, once, which is unusual for me or maybe anybody to do when reading a book, alone. I can't say, however, that my life was substantially enriched by reading it, nor that I learned anything except what kind of stuff people were reading and writing in the late 60s and early 70s.

Part of the reason that I feel reluctant to go into detail about the novel (is it one?) is that there's some stuff in there that I'm just not comfortable with. The way women are depicted in this book is both incorrect and idiotic, but to a certain, much more flattering extent, so is that of the men. The women that Brautigan writes about, here and elsewhere, seem to have two things in common: they're all beautiful without knowing or caring, and they're all rutting and looking ready to copulate with the next male (regardless of personal endowments) that they come across. I don't think of myself as altogether one of the "new men" which used to be talked about, but all the same I just feel kind of uncomfortable about this stuff. Or am I just a prude?

That would surprise me: I think Brautigan is, in a very pleasant and likeable way, a depraved chauvinist. And one who very clearly demonstrates this fact. But if we held every writer accountable for that or similar crimes, where we would we be? Without Hemingway, Roth (Philip and Joseph), Bellow (probably), Nabokov (almost certainly), Stendhal, Waugh (maybe we'd be better off here, guilty pleasures aside?), Burroughs (for sure), Patricia Highsmith (the worst of them all) and the list could go on, and on, and on. I for one am not willing to put all these against the wall at the expense of not being able to read them because of "ideological" or "moral" concerns.

Hawkline--and perhaps Brautigan's ouevre in general--is purposefully picayune, even frivolous. Maybe Brautigan thought this was exactly the sort of book that people needed at the time; maybe he felt these things reflected the "spirit of the age"; maybe Brautigan was just some kind of solipsistic comedian, an existential jester who confused himself with a protagonist. From what I've read about his other books and the way he's regarded (and who he is regarded by) I have to tend towards the last explanation, but clearly the 60s and the resulting come-down are to blame as well, perhaps even for Brautigan's death a decade and a half after the Summer of '69.

Wednesday, February 16, 2011

Guilty Pleasure of the Over-Read: Wilkie Collins's "The Woman in White"

I've just finished rereading The Woman in White for the third time. It's still good: still intense, still exciting--and still one of the best thrillers ever written after more than 150 years. Also, this is that rarest of things: a really entertaining, well-plotted novel with romance and mystery that English majors don't feel guilty about enjoying.

It's not too much to say that Woman is one of (if not the) prototypes for a large number of the popular novels of today. Though having celebrated its sesquicentennial, it nonetheless feels very modern and familiar in many respects. Not all of them for the best.

But Collins partially redeems his often fanciful plot choices and highly-polarized characters through the byzantine, even baroque structure of his narrative. He is also one of the first in literature to let a wide range of characters from a variety of social backgrounds speak and tell their own stories in their own voices.

This is, perhaps, Collins's great innovation. He certainly thought so. There is the perhaps unavoidable stench of "improvement" or "enhancement" of the voices--it kind of reminds me of how Bellow's characters are invariably described early on as "first-class noticers" (Wood)--but for the most part, and to a very great degree considering the quite low standards of the day in this and related genres, he pulls it off.

One of the best examples comes somewhere after the mid-point of the novel, when the former cook at Count Fosco's rented house in St. John's Wood relates what she knows to some sort of legal clerk. In this short section, Collins takes on the perspective and voice of an uneducated person, a person who could hardly have been less like himself, and does a fine job both with the point of view and the language. He even has the cook ask, though not in so many words, that her vocabulary and grammar be corrected in the taking down of her statement, thus providing a credible alibi for a more readable, less colloquial text than we might have expected otherwise.

There are many drawbacks to the novel, many aspects that irritate a modern reader and also much that is objectionable on artistic terms, but it should be borne in mind that this is one of the few works of literature of any value produced in its time and place, and furthermore that the book was intended as a popular entertainment--compared to today's equivalents (James Patterson, for example) Collins is a writer of great sympathy, vision and subtlety, not to mention the innovative nature of his work which we've already touched on.

Having sung it some praises, I'd now like to move on to some things that irritate me about The Woman in White--though bear in mind that some or all of these will have a lot to do with the socio-historical context that Collins was writing within.

For one thing, Laura, "Lady Laura", kind of pisses me off. This is primarily because the actions, many of them desperate and arduous, of the two most sympathetic characters in the story--our two protagonists, really--are motivated by their deep and repeatedly-repeatedly-repeatedly reiterated love (in all its transcendent mid-Victorian purity) for this girl who is, as far as I'm concerned, a complete dead zone of expression, intellect or significance except in her much-reported and, frankly, overemphasized beauty--oh, and her enormous fortune.

In a sense, this novel is primarily interested in her--and she is the point at which everything in the story turns--primarily because she is rich. And at a level that is both basic and base, Victorian fiction as a whole is about money and very little else. When this kind of thing is faced up to and treated quite openly, things are a lot more bearable--thank you, Trollope. But even the hallowed and feared category/deity of "respectability" is very often defined by or contrasted with the economic fortunes of and forces in the lives of individuals and families.

There is also a kind of "crisis of masculinity" going on in this book, and in a lot of sensation fiction (at least from the few books I've read)--see Mr. Fairlie, for example. Men inflict much pain, misery and depredation on women--women are constantly at the mercy of men who are placed in positions of power over them arbitrarily, without any consideration of the men's merits, often merely as the result of a vacuum in some section of the family tree--but it is always implied that what's needed is a benevolent tyrant in place of the wicked one presently seated on whatever throne.

So in the end it's only really a half-crisis; in the end nothing radical is said or settled. There are problems in this novel and others of its ilk, sure; these contradictions are sometimes presented, sure, and even railed against on occasion--but that's about the extent of it.

The fundamental evil (to call it what it is) of these power structures is hardly assailed at all. The one sort-of exception to this is what I perceive as a latent, 19th-century Liberal critique of the aristocracy, esp. the lower aristocracy, that I see Collins as carrying out without, as it were, putting himself out in the open and in the line of fire, much like a grouse trying not to be murdered by a member of the House of Lords and his pack of gillies. However, what Collins feels about questions that might be but aren't necessarily related, such as the validity of the monarchy in a country with more-or-less universal male suffrage, I just don't know.

There are lots of other things I could tell you about and get bothered about all over again, but in a way they don't actually detract from the pleasure of the story. As long as you can still identify with the characters, in spite of their views and beliefs (many of which I'm convinced Collins himself disapproved of and expected us to as well), at least enough to care about what happens to them, then we're in, we're sold to Collins, who will proceed to (as he was fond of saying) make us cry, make us laugh, and make us wait.

One more thing (god, I could write a whole book on The Woman in White, but I suspect there are too many of those already) before I sign off: I think there's a stronger connection between the serialized novels and perhaps the reading of most fiction in the 19th century to today's narrative TV shows, than there is between the way they read then and we read now. Just an idea....

[Further Reading: For anyone who is (like me) too interested in this stuff, I recommend John Sutherland's essay "The Missing Fortnight" in his first collection of entertaining and illuminating inquiries into the minor and insignificant minutiae of 19th-century English novels, Is Heathcliff a Murderer? (pg. 117 in the first Oxford World's Classics edition).]

Tuesday, February 15, 2011

"Forty Years of Murder" by Prof. Keith Simpson

An ugly little man, very much in love with his attainment of position and influence within his profession both at home and abroad, Simpson is also very much preoccupied with the perfection of knowledge and analysis in his chosen field of endeavor, forensic science.

This book, written after his retirement from full-time public service at Guy's Hospital and London University (now University College London) includes his recollections, often in great technical detail, of the crimes he was involved with during his years of activity as one of Great Britain's--and the world's--preëminent (I'm thinking about this convention, which I have sometimes permitted myself to adopt since my parents first got me a subscriptions to the New Yorker--but I'm still a little uncomfortable about it) pathologists.

I have some suspicions regarding the exact authorship of the book, that is to say as to whether or not the book was effectively ghosted from transcripts and memoranda of interviews by some unacknowledged but hopefully well-remunerated Grub-worm. If this were so, it would explain two things which I find it hard to reconcile with the character of Simpson as demonstrated in this book:

First, the often overly-conversational style (which makes for good reading, don't get me wrong) suggests the spoken word of a well-schooled public person, though not the typical prose style would would expect to be affected by such an individual with that background; and secondly, there is so much bravura and often not-too-subtle self-congratulation that it seems as if someone has just let him go on a bit too much and then, either out of a sense of fidelity or pique at having to listen to such a person for hours and hours and hours, put it all in pretty much verbatim.

Then again, I could see the first being just a personality quirk born out of long years of what might be called "professional casualness" and a sense of his own greatness putting the man at ease about whatever he had to say, and the second could very likely be put down to either an editor's (lack of?) taste or temerity in the face of an insistent Professor Cedric Keith Simpson, OBE, FCRP, ABCDEFG....

Regardless, the book is a good one, and the stories it contains are intriguing, sometimes horrifying. Simpson was involved in many of the most famous and infamous cases of his day: "the Luton Sack Murder", "Acid Bath" Haigh, the Brothers Kray--he was even called all the way to the "West Indies" (British people are so cute sometimes!) to investigate some of the alleged crimes of the man known as "Michael X".

All these and many more are described--their lurid tabloid titles appended--along with a nice selection of photographs of crime scenes, evidence, tools of death, murderers alleged and convicted, and Simpson in the company of various august personages (including J. Edgard Hoover, fortunately out of drag) to indicate the esteem in which Simpson was held--and not just by himself.

All these and many more are described--their lurid tabloid titles appended--along with a nice selection of photographs of crime scenes, evidence, tools of death, murderers alleged and convicted, and Simpson in the company of various august personages (including J. Edgard Hoover, fortunately out of drag) to indicate the esteem in which Simpson was held--and not just by himself.

Books I Got for Less than $10, or Why Are We Still Reading These Things?

From a View to a Death by Anthony Powell

Teleny, of The Reverse of the Medal by Oscar Wilde (?--et al.?)

The Anatomy Lesson by Philip Roth

The Consul's File by Paul Theroux

Justine by Lawrence Durrell

The Manuscript Found in Saragossa by Jan Potacki

The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins

Can You Forgive Her? by Anthony Trollope

Duo by Colette

Yesterday, I mentioned in passing an essay by George Orwell entitled "Are Books Too Dear?". Orwell was concerned that people, working class people primarily, were unwilling to spend money on books because they were perceived as a costly luxury. He disagreed, and went to some lengths to prove his point. Not that I imagine it did much good.

Just as back then and even more so today, there are libraries aplenty where you can find lots to read for the cost of--most of the time--nothing at all, except late fines. But I'd just like to point out that today, for about what even the least affluent make in an hour, I bought nine books (second hand, all of them, but none in bad condition).

Some people might say that it's easy if you have the kind of taste that can be satisfied by getting an early-70s Penguin classic for half of $3.50. There is some truth in this. But even the most recent mass market fiction, bought used, will be about $3.50 to $4.00, trade paperbacks around $7.00 to $8.00, and hardback fiction $10 to $15. And roughly speaking, the prices for those books bought new will be, respectively, less than $8.00, $15, and $25.

Let's think about these numbers in relationship to another form of relatively inexpensive entertainment, DVDs. A new DVD usually goes for somewhere between $20 and $30. Assuming the movie's running time is two hours, that's two hours of entertainment for about $25. Granted, there are often extras that some people enjoy watching, and somebody can always watch that movie again and again until it's too scratched or the technology becomes obsolete. Even if you rent that new movie, it will cost about $5.00.

The average book (although this varies much more than is the case with movies) probably takes most people four to eight hours. I'm not going to try to point out any of the obvious extrapolations; anybody interested enough already sees the point.

All of this is, however, just a lot of hot air coming from a person who likes to read and views books not as some kind of unusual luxury but as a household good to be stocked. The fact is that most people just don't think about books this way. There used to be some validity, and there probably still is, to the truism that middle class people appreciated literature as much or more than most, partly because it was part of the culture that separated them from those below them and part of the process (in terms of education) that maintained them in their socio-economic position and might allow them to rise higher.

In a sense, books were necessary for a large portion of society, and reading and comprehending texts of some length was a skill and means of advancement and self-education. In our much more multimedia culture today, this is no longer as true, and this fact can be seen not just elsewhere but within books as they are published today--just pick up, if you don't like the rest of us already have one, a copy of one the For Dummies or Complete Idiot's Guide books.

I think that it's not too much to say that the changes alluded to above have made reading less relevant. That doesn't mean that reading is irrelevant, but it does mean that come of the emphasis put on it is probably anachronistic and even reactionary. The fact is that new horizons have opened up for new kinds of literacy, some of them more intuitive in their grammar (film, the Internet) than old-fashioned linear narratives of the type found in most books.

People who love reading have to wake up to two (relatively) new truths: reading isn't the act that it once was, because the forces that mould the history of civilization (whatever they are) have changed its context as much as the behavior viewed in isolation may appear the same; and this rather radical alteration has, in a sense, freed language and literature from many of it's former duties and responsibility.

I honestly don't know if Joyce could have written what he did before radio; I'm fairly sure there would be no Ballard without TV, no Burroughs without film. At least, if it weren't for these new visual media, I don't see why we would have been interested in even needed them as much.

Perhaps I go too far in that last paragraph, but I'm stepping onto that ledge because I know there are points to be made out there.

Teleny, of The Reverse of the Medal by Oscar Wilde (?--et al.?)

The Anatomy Lesson by Philip Roth

The Consul's File by Paul Theroux

Justine by Lawrence Durrell

The Manuscript Found in Saragossa by Jan Potacki

The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins

Can You Forgive Her? by Anthony Trollope

Duo by Colette

Yesterday, I mentioned in passing an essay by George Orwell entitled "Are Books Too Dear?". Orwell was concerned that people, working class people primarily, were unwilling to spend money on books because they were perceived as a costly luxury. He disagreed, and went to some lengths to prove his point. Not that I imagine it did much good.

Just as back then and even more so today, there are libraries aplenty where you can find lots to read for the cost of--most of the time--nothing at all, except late fines. But I'd just like to point out that today, for about what even the least affluent make in an hour, I bought nine books (second hand, all of them, but none in bad condition).

Some people might say that it's easy if you have the kind of taste that can be satisfied by getting an early-70s Penguin classic for half of $3.50. There is some truth in this. But even the most recent mass market fiction, bought used, will be about $3.50 to $4.00, trade paperbacks around $7.00 to $8.00, and hardback fiction $10 to $15. And roughly speaking, the prices for those books bought new will be, respectively, less than $8.00, $15, and $25.

Let's think about these numbers in relationship to another form of relatively inexpensive entertainment, DVDs. A new DVD usually goes for somewhere between $20 and $30. Assuming the movie's running time is two hours, that's two hours of entertainment for about $25. Granted, there are often extras that some people enjoy watching, and somebody can always watch that movie again and again until it's too scratched or the technology becomes obsolete. Even if you rent that new movie, it will cost about $5.00.

The average book (although this varies much more than is the case with movies) probably takes most people four to eight hours. I'm not going to try to point out any of the obvious extrapolations; anybody interested enough already sees the point.

All of this is, however, just a lot of hot air coming from a person who likes to read and views books not as some kind of unusual luxury but as a household good to be stocked. The fact is that most people just don't think about books this way. There used to be some validity, and there probably still is, to the truism that middle class people appreciated literature as much or more than most, partly because it was part of the culture that separated them from those below them and part of the process (in terms of education) that maintained them in their socio-economic position and might allow them to rise higher.

In a sense, books were necessary for a large portion of society, and reading and comprehending texts of some length was a skill and means of advancement and self-education. In our much more multimedia culture today, this is no longer as true, and this fact can be seen not just elsewhere but within books as they are published today--just pick up, if you don't like the rest of us already have one, a copy of one the For Dummies or Complete Idiot's Guide books.

I think that it's not too much to say that the changes alluded to above have made reading less relevant. That doesn't mean that reading is irrelevant, but it does mean that come of the emphasis put on it is probably anachronistic and even reactionary. The fact is that new horizons have opened up for new kinds of literacy, some of them more intuitive in their grammar (film, the Internet) than old-fashioned linear narratives of the type found in most books.

People who love reading have to wake up to two (relatively) new truths: reading isn't the act that it once was, because the forces that mould the history of civilization (whatever they are) have changed its context as much as the behavior viewed in isolation may appear the same; and this rather radical alteration has, in a sense, freed language and literature from many of it's former duties and responsibility.

I honestly don't know if Joyce could have written what he did before radio; I'm fairly sure there would be no Ballard without TV, no Burroughs without film. At least, if it weren't for these new visual media, I don't see why we would have been interested in even needed them as much.

Perhaps I go too far in that last paragraph, but I'm stepping onto that ledge because I know there are points to be made out there.

Monday, February 14, 2011

BOOKS EVERYBODY SHOULD READ: George Orwell's Essays

Kind of obvious, maybe. I mean, everybody who's graduated from a high school in the US is liable to have read not one but two books by this great writer. Ironically, they're both works of fiction, which frankly was not what Orwell was best at.

His other novels are all interesting, amusing, and sometimes more: in particular, the melancholic autobiographical Keep the Aspidistra Flying and the sweltering if somewhat undercooked Burmese Days are well worth there place in print all these years later, though they remain there largely due to the success of an allegorical fable and a piece of dystopian sci-fi, the import of each neglected and subsumed by the system that routinely teaches our children how to misread them.

However, it's Orwell's non-fiction that really made him an important force--not "merely" a writer--in the 20th century. Is there any more important writer of non-fiction? Let me know if you think so. Down and Out in Paris and London, Homage to Catalonia and The Road to Wigan Pier are three of the best and most significant works of literature in the last hundred years and more. If anybody disagrees, we can go a few rounds.

Though most of his books have been widely available, and never to my knowledge out of print in his own UK (which god knows has better reason that anybody else to hate him back) many of his essays and in particular his more ephemeral writings (book reviews, columns, etc.) remained in large part uncollected. (I'll just mention here that there's a really interesting group of notes, transcripts and the like available from his time at the BBC--at the goddamn BBC!--you can still pick up 2nd hand. I actually bought a copy in Oklahoma City once, so that should give you an idea.)

This collection, published a few years ago in the US and I have no idea when in the UK, remedies this situation for the most part--it even goes so far as to include an unfinished article/essay sniping at Evelyn Waugh and his puny, hollow Catholicism. Good stuff. No doubt the fact that he was unable to complete it on his deathbed will be found reassuring to clerical child-rapists, their supporters, those who encourage the spread of AIDS in the Third World (yes, Third World, not "Global South") through the discouragement of safe sex, and that gay-hating fop, formerly of the Wehrmacht (unfair of me, I know, but the rest isn't), now prancing in robes under the soubriquet Benedict XVI. But what should one expect from sequels?

Alas, I digress. Although Orwell's essays are hardly unknown, and some of them ("Shooting an Elephant", "A Hanging", and esp. "Politics and the English Language") are among the most influential models of the form, much of what he produced is neglected. And produce much he did, as one ought to expect from an acknowledged past-master of something relatively brief and financially viable: my edition, published by that the always wonderful and beautiful Everyman's Library, runs to 1370 pages--longer or nearly as long as many editions of the Bible. Fittingly.

In particular, I'd like to draw people's attention to "Confessions of a Book Reviewer", "Are Books Too Dear?", "Raffles and Miss Blandish", "You and the Atom Bomb", "Boys' Weeklies", and "Inside the Whale". Oh yes, and all the others. Fortunately for those who can't just take my word for it and pay the $40.00 or whatever the book costs now, all this and much, much more (as Laurie Taylor says) is available here (sadly, it is no longer a pirate Russian site mirroring the material out of the Western copywright orbit...).

Before I go, maybe I should say actually why everybody should read George Orwell's essays. To be honest, I feel like the case shouldn't have to be made to any sane, democratically-minded human being. There being an unfortunate dearth of such individuals, esp. in my neck of the woods, I'll just say this, briefly: Orwell brought a new kind of conscience and moral seriousness combined with genuinely great prose style to a journalistic situation that badly needed them, at a crucial moment in history.

But his work needs to be reread today because so many of his analyses shine light on our modern political situations and the danger of both the right and the left, and point out the shell game played between the "extremes" by parties of power, esp. in countries like his and mine.

Not much has changed, and not much has stayed the same. Orwell keeps us on our toes, ready for action, ready to challenge received notions, whether they be the intelligentsia's love affair with Soviet Russia in the 30s or the use of scare-words like "terrorism" as a means of compelling consent in democratic societies today.

P.S. I'd just like to say that on my desk sits a small collection of books used for reference, though I suppose I'm maintaining an anachronism by using, for example, printed atlases. Let the future judge me, as I'm sure it will judge us all. Anyway, included in this group are: a relatively recent edition of Webster's, the Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology, Cassell's Latin Dictionary, Eco's The Open Work, and a few others. One of these others, and the one I have read and carried with me the most in my life, is my Everyman's edition of Orwell's Essays. It's that good and that important, that I consider a book made up to a large extent of stuff published in long-defunct newspapers and magazines to be an essential reference for my life. Please. Do. Read it.

His other novels are all interesting, amusing, and sometimes more: in particular, the melancholic autobiographical Keep the Aspidistra Flying and the sweltering if somewhat undercooked Burmese Days are well worth there place in print all these years later, though they remain there largely due to the success of an allegorical fable and a piece of dystopian sci-fi, the import of each neglected and subsumed by the system that routinely teaches our children how to misread them.

However, it's Orwell's non-fiction that really made him an important force--not "merely" a writer--in the 20th century. Is there any more important writer of non-fiction? Let me know if you think so. Down and Out in Paris and London, Homage to Catalonia and The Road to Wigan Pier are three of the best and most significant works of literature in the last hundred years and more. If anybody disagrees, we can go a few rounds.

Though most of his books have been widely available, and never to my knowledge out of print in his own UK (which god knows has better reason that anybody else to hate him back) many of his essays and in particular his more ephemeral writings (book reviews, columns, etc.) remained in large part uncollected. (I'll just mention here that there's a really interesting group of notes, transcripts and the like available from his time at the BBC--at the goddamn BBC!--you can still pick up 2nd hand. I actually bought a copy in Oklahoma City once, so that should give you an idea.)

This collection, published a few years ago in the US and I have no idea when in the UK, remedies this situation for the most part--it even goes so far as to include an unfinished article/essay sniping at Evelyn Waugh and his puny, hollow Catholicism. Good stuff. No doubt the fact that he was unable to complete it on his deathbed will be found reassuring to clerical child-rapists, their supporters, those who encourage the spread of AIDS in the Third World (yes, Third World, not "Global South") through the discouragement of safe sex, and that gay-hating fop, formerly of the Wehrmacht (unfair of me, I know, but the rest isn't), now prancing in robes under the soubriquet Benedict XVI. But what should one expect from sequels?

Alas, I digress. Although Orwell's essays are hardly unknown, and some of them ("Shooting an Elephant", "A Hanging", and esp. "Politics and the English Language") are among the most influential models of the form, much of what he produced is neglected. And produce much he did, as one ought to expect from an acknowledged past-master of something relatively brief and financially viable: my edition, published by that the always wonderful and beautiful Everyman's Library, runs to 1370 pages--longer or nearly as long as many editions of the Bible. Fittingly.

In particular, I'd like to draw people's attention to "Confessions of a Book Reviewer", "Are Books Too Dear?", "Raffles and Miss Blandish", "You and the Atom Bomb", "Boys' Weeklies", and "Inside the Whale". Oh yes, and all the others. Fortunately for those who can't just take my word for it and pay the $40.00 or whatever the book costs now, all this and much, much more (as Laurie Taylor says) is available here (sadly, it is no longer a pirate Russian site mirroring the material out of the Western copywright orbit...).

Before I go, maybe I should say actually why everybody should read George Orwell's essays. To be honest, I feel like the case shouldn't have to be made to any sane, democratically-minded human being. There being an unfortunate dearth of such individuals, esp. in my neck of the woods, I'll just say this, briefly: Orwell brought a new kind of conscience and moral seriousness combined with genuinely great prose style to a journalistic situation that badly needed them, at a crucial moment in history.

But his work needs to be reread today because so many of his analyses shine light on our modern political situations and the danger of both the right and the left, and point out the shell game played between the "extremes" by parties of power, esp. in countries like his and mine.

Not much has changed, and not much has stayed the same. Orwell keeps us on our toes, ready for action, ready to challenge received notions, whether they be the intelligentsia's love affair with Soviet Russia in the 30s or the use of scare-words like "terrorism" as a means of compelling consent in democratic societies today.

P.S. I'd just like to say that on my desk sits a small collection of books used for reference, though I suppose I'm maintaining an anachronism by using, for example, printed atlases. Let the future judge me, as I'm sure it will judge us all. Anyway, included in this group are: a relatively recent edition of Webster's, the Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology, Cassell's Latin Dictionary, Eco's The Open Work, and a few others. One of these others, and the one I have read and carried with me the most in my life, is my Everyman's edition of Orwell's Essays. It's that good and that important, that I consider a book made up to a large extent of stuff published in long-defunct newspapers and magazines to be an essential reference for my life. Please. Do. Read it.

IN PRAISE OF: E. F. Bleier

Nobody who only reads good, solid, literary prose of a serious nature is likely to have any idea who this post is about. On the other hand, people who only read shitty contemporary sci-fi and fantasy novels (my brother Daniel, for example) are equally unlikely to recognize the name. Basically, nobody has any reason to know anything about E. F. Bleier, and if I spent my time more wisely, I probably wouldn't either.

However, I do. And I love him. Or did, until this past summer when he died without me or anybody else noticing, at the grand old age of 90. Good going, Everett.

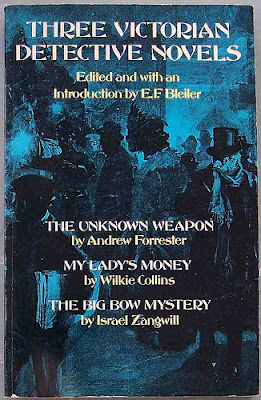

I think that Bleier was an American, but I don't really care, and he might as well have been British: right now on the shelves in my bedroom I happen to have three books edited by him--Three Gothic Novels, Three Victorian Detective Novels, and The King in Yellow and Other Horror Stories by Robert W. Chambers, selected by Bleier. All of these volumes have authoritative introductions setting out the context and significance of the works they precede.

In addition to his editorial work, Bleier wrote something called Firegang: A Mythic Fantasy that I suspect was best left unpublished (it only came out in 2006 from a tiny SF press) but who knows? Maybe it's great. Doesn't matter, because even if proof came out tomorrow that he was secretly a Nazi war criminal, having commanded an Einsaztgrüpen in the General Government during the winter of 1941, killing Jewish and dark-haired Poles (including women and, naturally, children) just to keep warm by burning their bodies arranged into huge and architecturally magnificent bonfires, I honestly wouldn't be able to help but still be glad that he'd lived--and all because of stuff he didn't even write. Allow me to explain.

Here's how it works: lots of people write books. Some people read some of these books, sometimes a lot of people read a book soon after it comes out, making it "popular". But then as time goes on, fewer and fewer people read those books, distracted as they are by something sparkling/something new. Some people do keep reading them, because they happen to find them in a used bookstore, because somebody recommends them, because of this, because of that--but basically, less and less, fewer and fewer. Some books come back with a vengeance under the steam of what I believe are called "the arbiters of public taste" or "gatekeepers of the canon" or "Harold Bloom". But they don't read everything, and funnily enough sometimes the people who read the most have the least catholic (small "c"!) tastes.

But none of this to say that some of the books that got read when they first came out only some time thereafter to be all but forgotten, or even books that hardly got or didn't get read at all when first published (Moby Dick) aren't any good. Sometimes, depending on where you're standing in time and where you're looking back to, quite the opposite is true.

So sometimes there are books, books which are very good or at least very notable, either influential or heralding something new or as artifacts of their time or just (the best) because of their weird, uncategorizable nature, that get lost between the cracks in the floorboards of the library of the mainstream's literary consciousness, except that such a metaphor is both grotesque and unlikely, and so someone has to go and rescue them and say, "Look! Look at this! Can't you see?!"

Only, nobody has to do that. And if someone didn't, all we'd have today are a few printed copies left over that were never used to wipe some child's ass and Project Gutenberg files that no one ever reads, not only but partly because they are unreadable. The someone who did--well, one of the someones--was E. F. Bleier. If I haven't already said it, thank you.

Things I have to thank Bleier for: I read Byron's "Fragment of a Novel" (probably the first vampire fiction ever written) in one of his books, included to give some context to the painful but interesting Vampyre of Polidori; in the same volume, Vathek--I might never have read Vathek (!) if it weren't for him, and that is was crazy, wonderful book, a book one could say, if one was tempted to say things like this, isolated like an island (like the Isle of Redonda, perhaps?) from the rest of English literature; the first police detective protagonist (and first female detective, in the same person) in The Unknown Weapon by Andrew Forrester, Jr. ("Little is known of the author, beyond the titles of his three obscure books of crime and detection and the fact that he read Poe."); Wilkie Collins' My Lady's Money, not published anywhere else that I know of (a post or posts on my exhilarating, torrid re-reading of Woman in White coming soon); and so, so much more: Max Carrados, for example, and I also first read Algernon Blackwood's best stuff in a selection he edited, etc.

Why did Bleier never edit a book of M. R. James' ghost stories (some of my favorite--or, I'll just come out and say it: my favorite bedtime stories ever)? I'm just curious. Maybe he didn't like them, or he didn't like James personally, if they ever met, or maybe James' stuff wasn't going cheap enough or in the public domain so that Dover (who Bleier did his best work for, or at the work that I and most people who've heard of him known him from) couldn't get their hands on it. Regardless, I'd like to read something that Bleier had to say about James and that ghost story tradition--if any knows of anything, please let me know.

Well, that's enough and certainly not enough on this guy, who wrote so much about what other people wrote. I wonder how he actually managed to earn a living, but then again I suspect that mysterious process will forever remain obscure to me, particularly in regard to my own life.

However, I do. And I love him. Or did, until this past summer when he died without me or anybody else noticing, at the grand old age of 90. Good going, Everett.

I think that Bleier was an American, but I don't really care, and he might as well have been British: right now on the shelves in my bedroom I happen to have three books edited by him--Three Gothic Novels, Three Victorian Detective Novels, and The King in Yellow and Other Horror Stories by Robert W. Chambers, selected by Bleier. All of these volumes have authoritative introductions setting out the context and significance of the works they precede.

In addition to his editorial work, Bleier wrote something called Firegang: A Mythic Fantasy that I suspect was best left unpublished (it only came out in 2006 from a tiny SF press) but who knows? Maybe it's great. Doesn't matter, because even if proof came out tomorrow that he was secretly a Nazi war criminal, having commanded an Einsaztgrüpen in the General Government during the winter of 1941, killing Jewish and dark-haired Poles (including women and, naturally, children) just to keep warm by burning their bodies arranged into huge and architecturally magnificent bonfires, I honestly wouldn't be able to help but still be glad that he'd lived--and all because of stuff he didn't even write. Allow me to explain.

Here's how it works: lots of people write books. Some people read some of these books, sometimes a lot of people read a book soon after it comes out, making it "popular". But then as time goes on, fewer and fewer people read those books, distracted as they are by something sparkling/something new. Some people do keep reading them, because they happen to find them in a used bookstore, because somebody recommends them, because of this, because of that--but basically, less and less, fewer and fewer. Some books come back with a vengeance under the steam of what I believe are called "the arbiters of public taste" or "gatekeepers of the canon" or "Harold Bloom". But they don't read everything, and funnily enough sometimes the people who read the most have the least catholic (small "c"!) tastes.

But none of this to say that some of the books that got read when they first came out only some time thereafter to be all but forgotten, or even books that hardly got or didn't get read at all when first published (Moby Dick) aren't any good. Sometimes, depending on where you're standing in time and where you're looking back to, quite the opposite is true.

So sometimes there are books, books which are very good or at least very notable, either influential or heralding something new or as artifacts of their time or just (the best) because of their weird, uncategorizable nature, that get lost between the cracks in the floorboards of the library of the mainstream's literary consciousness, except that such a metaphor is both grotesque and unlikely, and so someone has to go and rescue them and say, "Look! Look at this! Can't you see?!"

Only, nobody has to do that. And if someone didn't, all we'd have today are a few printed copies left over that were never used to wipe some child's ass and Project Gutenberg files that no one ever reads, not only but partly because they are unreadable. The someone who did--well, one of the someones--was E. F. Bleier. If I haven't already said it, thank you.

Things I have to thank Bleier for: I read Byron's "Fragment of a Novel" (probably the first vampire fiction ever written) in one of his books, included to give some context to the painful but interesting Vampyre of Polidori; in the same volume, Vathek--I might never have read Vathek (!) if it weren't for him, and that is was crazy, wonderful book, a book one could say, if one was tempted to say things like this, isolated like an island (like the Isle of Redonda, perhaps?) from the rest of English literature; the first police detective protagonist (and first female detective, in the same person) in The Unknown Weapon by Andrew Forrester, Jr. ("Little is known of the author, beyond the titles of his three obscure books of crime and detection and the fact that he read Poe."); Wilkie Collins' My Lady's Money, not published anywhere else that I know of (a post or posts on my exhilarating, torrid re-reading of Woman in White coming soon); and so, so much more: Max Carrados, for example, and I also first read Algernon Blackwood's best stuff in a selection he edited, etc.

Why did Bleier never edit a book of M. R. James' ghost stories (some of my favorite--or, I'll just come out and say it: my favorite bedtime stories ever)? I'm just curious. Maybe he didn't like them, or he didn't like James personally, if they ever met, or maybe James' stuff wasn't going cheap enough or in the public domain so that Dover (who Bleier did his best work for, or at the work that I and most people who've heard of him known him from) couldn't get their hands on it. Regardless, I'd like to read something that Bleier had to say about James and that ghost story tradition--if any knows of anything, please let me know.

Well, that's enough and certainly not enough on this guy, who wrote so much about what other people wrote. I wonder how he actually managed to earn a living, but then again I suspect that mysterious process will forever remain obscure to me, particularly in regard to my own life.

Nick Hornby's "Housekeeping vs. The Dirt"

Great. Just great. Totally un-intellectual and never above itself, often below (he quotes thusly from Philip Larkin's letters: "I think this poem is really bloody cunting fucking good." "Your letter found me last night when I came in off the piss. I had spewed out of a train window and farted in the presence of ladies and generally misbehaved myself.""Katherine Mansfield is a cunt.") and just generally a lot of fun, as you can see.

Everybody should read his column in the Believer but then I guess that would mean that people were actually reading that magazine, which is just too inconceivable, as Hornby himself points out. I actually laughed a few times while reading this book, which I don't usually do even when I think a book is funny.

There's lots of stuff about how the UK isn't like the US, which is true but only noticeable to them and to us: to everyone else, we're basically the same game, and all of us are right. Also included: rants against fiction about literature, matters literary and the literati; constant sarcasm and irony; ready admissions that he just didn't finish a book because it was too boring or maybe over his head or that he never even started it.

All this and much, more more abide inside the Euro-flap covers of this delightful book, praised to the heavens or their secular equivalent by every left-wing progressive news source from here to there: the back has blurbs from Salon.com, the Boston Globe, NPR, the SF Chronicle, the Austin Chronicle, and of course, of course, the Guardian.

Everybody should read his column in the Believer but then I guess that would mean that people were actually reading that magazine, which is just too inconceivable, as Hornby himself points out. I actually laughed a few times while reading this book, which I don't usually do even when I think a book is funny.

There's lots of stuff about how the UK isn't like the US, which is true but only noticeable to them and to us: to everyone else, we're basically the same game, and all of us are right. Also included: rants against fiction about literature, matters literary and the literati; constant sarcasm and irony; ready admissions that he just didn't finish a book because it was too boring or maybe over his head or that he never even started it.

All this and much, more more abide inside the Euro-flap covers of this delightful book, praised to the heavens or their secular equivalent by every left-wing progressive news source from here to there: the back has blurbs from Salon.com, the Boston Globe, NPR, the SF Chronicle, the Austin Chronicle, and of course, of course, the Guardian.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)